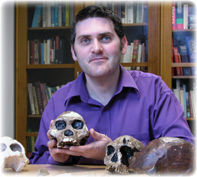

| Career Profile: Dr Darren Curnoe Jacqueline Nguyen Dr Darren Curnoe is a lecturer in the Department of Anatomy, in the School of Medical Sciences at UNSW. His research interests fall within three major areas: human evolution, skeletal biology of hunter-gatherers, and comparative anatomy and systematics of primates. Dr Darren Curnoe studied biological anthropology at the Australian National University, graduating with first class honours. He went on to complete a PhD in palaeoanthropology and geochronology at the Institute of Advanced Studies at the ANU. Curnoe spent 2002 in Johannesburg, South Africa as a post-doctorate fellow in the School of Anatomical Sciences at the University of Witwatersrand, working with Professor Phillip Tobias. There he worked on an anatomical reconstruction of a Homo habilis fossil, dated from about 1.5 million years ago (MYA). He then trained to teach anatomy and joined UNSW in November 2002.

Thoughts on Biological Anthropology Biological anthropologists study how evolution has shaped us and compare the way we look and behave with other primates. Curnoe believes that biological anthropology is important because it allows us to gain insight into our own existence. "Evolution is one of several ways of understanding ourselves, but itís an important one. Many of us are interested in the human condition, and itís interesting to think about why we are the way we are from an evolutionary perspective." Philosophers think about the human mind and condition; psychologists think about human thought and behaviour; and sociologists think about the way we structure ourselves in communities and societies. There are many similarities between these schools of thought and that of biological anthropologists. ďAnthropology is also important because we know more about our anatomy, behaviour, genetics, diseases, pathology and evolution more than any other species. That makes humans a very important test case for evolutionary biology. If we can truly understand our own evolution, then I think we will gain a lot of insights into the mechanisms, the broad picture of evolution, why evolution works.Ē

When asked why he thought science was important, Darren answered, ďWhat impresses me the most about science is the scientific method. It differs from ordinary thinking in that we set out to reject ideas. We propose a hypothesis, then go about trying to show itís wrong. Thatís its strength. In ordinary thinking we donít tend to do that. We just believe things and see things that fit the way we think, or the way we believe. Thatís whatís nice about science, you can approach the natural world and go about trying to understand it in a systematic and, as much as possible, an objective way to understand natural processes.Ē ďKarl Popper, a great scientific philosopher, stated that what makes a good scientific hypothesis is that it stands the test of time. In other words, the reason why a hypothesis is accepted, or becomes a scientific law, is because it survived repeated attempts to show itís wrong. The fascinating thing about science is that many people have tried to show it as wrong and have been unable to refute it. The real strength of science is the way we go about trying to show that things are wrong and after a time, if we canít, then we realise thereís obviously something to it, even though later on some information might come along and we might be able to reject it. And itís true that weíve built up this incredible body of knowledge and understanding about the world.Ē ďI think a lot of people who donít practice science see it as a cold, clinical way of thinking. But itís not; itís about the passion of discovery. Many scientists have a true sense of awe of nature, thatís almost spiritual. I think that the natural world is incredible and I feel a real sense of awe and mystery about the natural world, and I want to understand that. And the only rational way I can do that is to use the scientific method.Ē Darren also believes imagination is important in science. ďI think the difference between an average scientist and a good scientist is imagination. Itís not about whether youíre technically competent or good at testing theories, itís about having imagination. A lot of people donít realise it, but science is a creative process, being able to look at facts, analyse facts, look at patterns, interpret, come up with explanations -- all those sorts of things take a lot of creativity.Ē ďThe next step is when you go about testing it in a rational way, is where the hard, systematic, objective part comes in. But to get there, and come up with sensible explanations or hypotheses youíve got to have some imagination. It has a strong creative part to it as well, which is very satisfying too.Ē

When asked about the best and worst aspects of his job Darren replied, ďThere arenít many things about my job I donít like and thatís in all honesty.Ē ďI love the research, thatís what really drives me. I have a real passion for the study of human evolution. I get very enthusiastic about it. Itís what keeps me going at the end of the day, but I really enjoy teaching too. I love helping students learn. Thatís a lot of fun and itís very satisfying, particularly when students are enjoying what theyíre learning.Ē Darren says the worst aspect of his job is that ďsometimes things get too busy. I donít always get time to put my feet up and read journal articles, or think about research problems. Things are sometimes rushed because thereís a constant heavy teaching load and administrative duties.Ē Getting grant money is also a downside to Darrenís job. ďIn an area like mine there isnít much money around. Itís very competitive and hard to get money.Ē ďBut

Iíd recommend the career for anyone who has the passion

for research and finds an area that theyíre really interested

in. Itís worth putting in the hard work, getting through

the post-grad and post-doc, to get a job where you know

that youíre doing something you love. I donít have a hobby;

this is my job and my hobby. I feel very privileged to

be able to do what I love for a living.Ē Wright, L. (2003) Shaking the Evolutionary Tree. UNSW Uniken Magazine, Issue 4. Curnoe, D. & Thorne, A. (2003) Number of Ancestral Human Species: A Molecular Perspective. Homo 53, 201-224 Thorne, A. Grün, R. Mortimer, G. Spooner, N.A. McCulloch, M. Taylor, L. and Curnoe, D. (1999) Australia's Oldest Human Remains: Age of the Lake Mungo 3 Skeleton. Journal of Human Evolution 36, 591-612.

Biological

anthropology: using biological principles and approaches

for the study of humans. Homo habilis: an early member of the human genus Homo, appearing in the fossil record about 2.5 MYA. Paleoanthropology: the study of early humans and non-human primates, and their evolution. Systematics: the study of the classification and evolutionary history of a species, or group of species.

|

OnSET is an initiative of the Science Communication Program

URL: http://www.onset.unsw.edu.au/ Enquiries: onset@unsw.edu.au

Authorised by: Will Rifkin, Science Communication

Site updated: 7 Febuary, 2006 © UNSW 2006 | Disclaimer

OnSET is an online science magazine, written and produced by students.

![]()

OnSET Issue 6 launches for O-Week 2006!

![]()

Worldwide

Day in Science

University

students from around the world are taking a snapshot

of scientific endeavour.

Sunswift

III

The UNSW Solar Racing Team is embarking

on an exciting new project, to design and build the

most advanced solar car ever built in Australia.

![]()

Outreach

Centre for Sciences

UNSW Science students can visit your school

to present an exciting Science Show or planetarium

session.

![]()

South

Pole Diaries

Follow the daily adventures of UNSW astronomers

at the South Pole and Dome C through these diaries.

News in Science

UNSW is not responsible for the content of

these external sites