Title:

Career

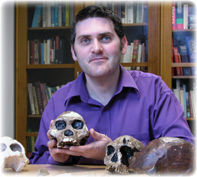

Profile: Dr Darren Curnoe

Author: Jacqueline

Nguyen

Category: Career Profile

Dr Darren Curnoe

is a lecturer in the Department of Anatomy, in the School

of Medical Sciences at UNSW. His research interests fall

within three major areas: human evolution, skeletal biology

of hunter-gatherers, and comparative anatomy and systematics

of primates.

Dr Darren

Curnoe studied biological

anthropology at the Australian National University, graduating

with first class honours. He went on to complete a PhD in

palaeoanthropology

and geochronology

at the Institute of Advanced Studies at the ANU. Curnoe spent

2002 in Johannesburg, South Africa as a post-doctorate fellow

in the School of Anatomical Sciences at the University of

Witwatersrand, working with Professor Phillip Tobias. There

he worked on an anatomical reconstruction of a Homo

habilis fossil, dated from about 1.5 million years ago

(MYA). He then trained to teach anatomy and joined UNSW in

November 2002.

Dr

Darren Curnoe |

Thoughts

on Biological Anthropology

Biological

anthropologists study how evolution has shaped us and compare

the way we look and behave with other primates. Curnoe believes

that biological anthropology is important because it allows

us to gain insight into our own existence. "Evolution

is one of several ways of understanding ourselves, but itís

an important one. Many of us are interested in the human condition,

and itís interesting to think about why we are the way we

are from an evolutionary perspective."

Philosophers

think about the human mind and condition; psychologists think

about human thought and behaviour; and sociologists think

about the way we structure ourselves in communities and societies.

There are many similarities between these schools of thought

and that of biological anthropologists.

ďAnthropology

is also important because we know more about our anatomy,

behaviour, genetics, diseases, pathology and evolution more

than any other species. That makes humans a very important

test case for evolutionary biology. If we can truly understand

our own evolution, then I think we will gain a lot of insights

into the mechanisms, the broad picture of evolution, why evolution

works.Ē

Thoughts on Science

When asked

why he thought science was important, Darren answered, ďWhat

impresses me the most about science is the scientific method.

It differs from ordinary thinking in that we set out to reject

ideas. We propose a hypothesis, then go about trying to show

itís wrong. Thatís its strength. In ordinary thinking we donít

tend to do that. We just believe things and see things that

fit the way we think, or the way we believe. Thatís whatís

nice about science, you can approach the natural world and

go about trying to understand it in a systematic and, as much

as possible, an objective way to understand natural processes.Ē

ďKarl

Popper, a great scientific philosopher, stated that what makes

a good scientific hypothesis is that it stands the test of

time. In other words, the reason why a hypothesis is accepted,

or becomes a scientific law, is because it survived repeated

attempts to show itís wrong. The fascinating thing about science

is that many people have tried to show it as wrong and have

been unable to refute it. The real strength of science is

the way we go about trying to show that things are wrong and

after a time, if we canít, then we realise thereís obviously

something to it, even though later on some information might

come along and we might be able to reject it. And itís true

that weíve built up this incredible body of knowledge and

understanding about the world.Ē

ďI think

a lot of people who donít practice science see it as a cold,

clinical way of thinking. But itís not; itís about the passion

of discovery. Many scientists have a true sense of awe of

nature, thatís almost spiritual. I think that the natural

world is incredible and I feel a real sense of awe and mystery

about the natural world, and I want to understand that. And

the only rational way I can do that is to use the scientific

method.Ē

Darren

also believes imagination is important in science. ďI think

the difference between an average scientist and a good scientist

is imagination. Itís not about whether youíre technically

competent or good at testing theories, itís about having imagination.

A lot of people donít realise it, but science is a creative

process, being able to look at facts, analyse facts, look

at patterns, interpret, come up with explanations -- all those

sorts of things take a lot of creativity.Ē

ďThe next

step is when you go about testing it in a rational way, is

where the hard, systematic, objective part comes in. But to

get there, and come up with sensible explanations or hypotheses

youíve got to have some imagination. It has a strong creative

part to it as well, which is very satisfying too.Ē

Best and worst aspects of his job

When asked

about the best and worst aspects of his job Darren replied,

ďThere arenít many things about my job I donít like and thatís

in all honesty.Ē

ďI love

the research, thatís what really drives me. I have a real

passion for the study of human evolution. I get very enthusiastic

about it. Itís what keeps me going at the end of the day,

but I really enjoy teaching too. I love helping students learn.

Thatís a lot of fun and itís very satisfying, particularly

when students are enjoying what theyíre learning.Ē

Darren

says the worst aspect of his job is that ďsometimes things

get too busy. I donít always get time to put my feet up and

read journal articles, or think about research problems. Things

are sometimes rushed because thereís a constant heavy teaching

load and administrative duties.Ē Getting grant money is also

a downside to Darrenís job. ďIn an area like mine there isnít

much money around. Itís very competitive and hard to get money.Ē

ďBut Iíd

recommend the career for anyone who has the passion for research

and finds an area that theyíre really interested in. Itís

worth putting in the hard work, getting through the post-grad

and post-doc, to get a job where you know that youíre doing

something you love. I donít have a hobby; this is my job and

my hobby. I feel very privileged to be able to do what I love

for a living.Ē

See OnSET's Chiselling

away at the traditional way of thinking

Further Reading

Wright,

L. (2003) Shaking the Evolutionary Tree. UNSW

Uniken Magazine, Issue 4.

Curnoe,

D. & Thorne, A. (2003) Number of Ancestral Human Species:

A Molecular Perspective. Homo 53,

201-224

Thorne,

A. Grün, R. Mortimer, G. Spooner, N.A. McCulloch, M.

Taylor, L. and Curnoe, D. (1999) Australia's Oldest Human

Remains: Age of the Lake Mungo 3 Skeleton. Journal of

Human Evolution 36, 591-612.

Glossary

Biological

anthropology: using biological principles and approaches

for the study of humans.

Geochronology:

the chronology of the earthís history as determined by geological

events

Homo

habilis: an early

member of the human genus Homo, appearing in the

fossil record about 2.5 MYA.

Paleoanthropology:

the study of early humans and non-human primates, and their

evolution.

Systematics:

the study of the classification and evolutionary history of

a species, or group of species.

|