|

Title:

Nanotechnology: Asking the Small Questions

Author: Stephen

Catchpole

Category: Current Affairs (feature article)

Molecular nanotechnology refers

to studies in the design and construction of objects on a

molecular scale. Though in its infancy, nanotechnology is

already being applied to produce a range of new materials

– from atomic-size solar cells1

and electrical circuits, to potential surface coatings for

use in clothing, paints and even future space habitation!2

|

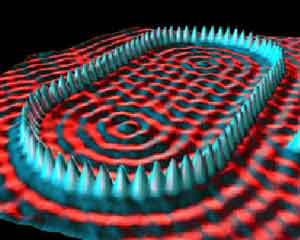

Scanning tunnelling microscope (STM) picture

of a stadium-shaped "quantum corral" made

by positioning iron atoms on a copper surface. ©

Courtesy of IBM

|

Soon scientists might be able to construct useful devices

from individual molecules, with a size in the order of tens

of microns. Compare that to a human hair, around one hundred

microns in diameter! Much research effort is being directed

in this area, with one lofty goal being the production of

miniature self-replicating robots, dubbed ‘nanites’.

As with

any technological breakthrough, the potential environmental

impact of nanites needs to be addressed before they are introduced.

Concerns have also been raised over what constitutes ethical

use of nanites, given that military and law enforcement authorities

have started to show interest. Already influential thinkers

and senior figures in the technology age have weighed in for

the debate over nanites, each with some compelling arguments.

Soon lines will be drawn in the sand – separating those who

see them as a harbinger of doom and those who believe they

will bring a new dawn for humanity.

Those who fear an apocalyptic event are actually led by influential

thinkers and technologists, hardly the ‘Luddites’ commonly

associated with criticism of science. Perhaps one of the most

outspoken advocates of technological caution is Bill Joy,

former Chief Scientist at Sun Microsystems. His article in

Wired Magazine called “Why the Future Doesn't Need Us” mounts

a strong case for prudence: “A bomb is blown up only once

- but one bot can become many, and quickly get out of control”.3

While in this case he is talking about using nanotechnology

to create weapons, he also emphasises the risk of a ‘grey

goo’ event – where due to a flaw in its design or programming,

a nanite reproduces itself until there are no raw materials

left, covering the earth with its ‘offspring’. The result

might not necessarily be grey or gooey – but it could lead

to mass extinction on Earth.

Michael

Crichton, a science-fiction author with a reputation for sticking

to issues near the cusp of development, has written a novel

called Prey, in which this grey goo phenomenon becomes a real

risk. In the pursuit of military technology and profit, scientists

create self-replicating nanites that escape the lab and begin

to decimate local wildlife. They spread exponentially like

bacteria but are eventually contained. Prey may be intended

as a cautionary tale; in fact, Crichton even includes this

warning in an introductory chapter called “Artificial Evolution

in the Twenty-first Century''.

Though

the focus of debate may be on military applications, nanites

will undoubtedly bring numerous other benefits to society

– allowing us to achieve things previously impossible. The

group who see only bright lights on the horizon contain individuals

no less prominent. Ray Kurzweil, who created the first reading

machine for the blind, has come to be one of the strongest

advocates of the Libertarian ideal in technology. In fact,

Joy's initial article was in response to Kurzweil's book,

The Age of Spiritual Machines, in which Kurzweil envisioned

a utopia brought about by technology. In this future, nanotechnology

would allow us to extend our life spans, as nanites roamed

through our bodies to cure disease.

Freeman

Dyson, a respected physicist and writer who was asked to debate

opposite Joy at the World Economic Forum in 2001, compares

banning nanotechnology to the efforts to ban the free press

in England in the seventeenth century. He takes the poet John

Milton's argument for books, that we “have a vigilant eye

how [they] demean themselves as well as men; and thereafter

to confine, imprison, and do sharpest justice on them as malefactors”.

Dyson

feels that scientists can be self-regulated and, only if they

prove themselves to be untrustworthy, should they be limited.4

To limit scientists now may possibly delay or deny us all

the future benefits of nanotechnology.

Many science

fiction authors see the evolution of nanotechnology materials

to be necessary for the evolution of humanity beyond its earthly

bounds. In his sequels to 2001: A Space Odyssey, Arthur C.

Clarke proposed a space elevator that would require materials

that are orders of magnitude stronger than steel as the cable.

NASA scientists believe they may have found this material

in carbon nanotubes, if they can successfully scale up production.

Using such a space elevator we could finally cut the cost

of getting into space to a level where human exploration of

the solar system would become affordable.5

In all

likelihood the way forward lies in the middle ground. The

social risks inherent in nanotechnology can be reduced if

policy makers act responsibly. The Foresight Institute, one

of the sponsors of a recent conference on nanotechnology,

has published a set of guidelines on molecular technology.6

These guidelines would require any self-replicating device

to be prevented from replicating through technological means

beyond the limits imposed upon it by its human creators. Nanites

would require specific 'vitamin' chemicals to reproduce, so

that if somehow they did not obey a command to stop reproducing

they would soon run out of raw materials. Code used to reproduce

nanites would be encrypted so that any random 'mutation' like

those that cause cancer in human cells would instead cause

the robot to stop working. The guidelines also recommend that

governments legislate against those who fail to follow these

guidelines.

In any

event, despite some advances, such as a robot arm now being

capable of producing a copy of itself out of spare parts,7

self-replication of the sort feared by Joy and others is still

years, or even decades from being possible. Technology to

manipulate matter at the molecular level with any degree of

precision is still in the realm of science fiction. However,

as the Pacific Research Institute suggests, ‘vehement’ debate

is inevitable when this technology comes closer.8

Given a fair chance, nanotechnology will change the world.

The question we must now ask is: “should we let it?”

Stephen

Catchpole is a Mechatronic Engineering Student at the University

of New South Wales, specialising in intelligent mobile robotics.

References

1. Peyton, C.

March 29, 2002, 'Researchers move closer to plastic, cheaper

solar power cells', The Sacramento Bee, [online at] http://www.sacbee.com/content/news/story/1987845p-2201460c.html

2. Britt, R.

April 23, 2001, Smart Coating Developed to Build Future Martian

Homes, [online] http://space.com/scienceastronomy/solarsystem/nano_mars_010423.html

[20/10/03]

3. Joy, B, April

2000, 'Why the future doesn't need us', [online], Wired 8.02,

http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/8.04/joy.html?pg=1

[20/10/03]

4. Freeman J.

Dyson, February 13, 2003, 'The future needs us', New York

Review of Books, [online at] http://www.nybooks.com/articles/16053

5. Macey, R,

September 20, 2003, 'Tie me to the moon', Sydney Morning

Herald, [online at] http://www.smh.com.au/articles/2003/09/19/1063625214015.html

6. Foresight

Guidelines on Molecular Technology, June 4, 2000, [online]

http://www.foresight.org/guidelines/current.html

[20/10/03]

7. Exponential

Assembly, Zyvex Corporation, 2003, [online] http://www.zyvex.com/Research/exponential.html

[20/10/03]

8. Reynolds,

G, November 2002, 'Forward to the future: Nanotechnology and

regulatory policy', Pacific Research Institute Briefing, [online

at] http://www.pacificresearch.org/pub/sab/techno/forward_to_nanotech.pdf

|