The

Scientific Method: Darwinism or Design Part 2

Darwin Fights Back

Ellie Pratt

Now that we have investigated what allows one theory

to gain validity and acceptance over others, does Darwin’s

account of evolution fit this framework of ‘good science’?

Claims that Darwinism is unscientific are most often made

by those who see it as an attack on their fundamental

religious beliefs.

The Creationist argument (and more recently that of proponents

of Intelligent Design) rests on misuse of Popperian falsification

and the misleading phrase that evolution is ‘just a theory’

and, therefore, not believable. The latter, as we have

seen, is an invalid argument. It is the inherent nature

of science that many argument are ‘just a theory’. This

status should not be seen as a negative thing; rather

it is one of the features that lend authority to science

– nothing is infallible, and as such, science must be

“self-correcting”. Intelligent Design proponents, though,

often present their theory as more scientific than Darwinian

evolution , contending that “science demands proof…[and]…proof

of evolution is not forthcoming” (Kitcher 1982:31).

Of course, we do not live long enough to see full-scale

evolution in progress, but we can test individually the

auxiliary hypotheses of which Darwinian evolution is composed.

The distinction drawn by Darwin’s opponents in contrasting

science with religion is too simple; it is not as easy

as saying that science is a matter of proof. Kitcher contends

that, for a theory to be “genuine[ly] scientific”, its

auxiliary hypotheses must have “observational consequences”

in order to be testable. Here, the strength of Darwinian

evolution can be seen, providing claims that are testable

and not as yet falsified.

|

The main tenet of Darwinian evolution is that change occurs in species gradually with the eventual result being the appearance of new species. This tenet rests on the fact that within a given population there will be inherent genetic variability. Some individuals within a population will possess favourable characteristics that make them ‘fitter’ in a given environment, and as a result produce more offspring, which will most likely carry those favourable variations. This process is natural selection, or ‘survival of the fittest’.

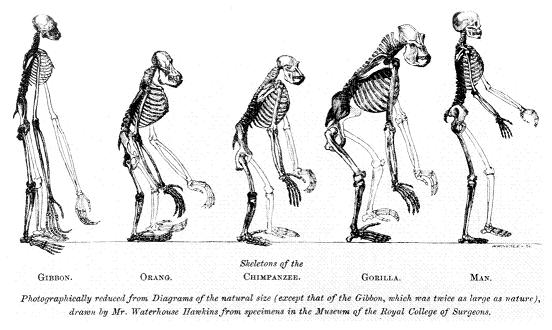

The scientific basis of Darwinism rests on five major pieces of evidence: palaeontology; biogeography; anatomy; embryology; and systematics. These areas form the auxiliary hypotheses of Darwinism and act as the test-pieces for claims arising from Darwin’s theory.

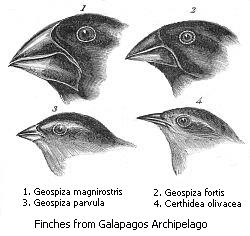

Darwin’s discussion of palaeontology is an example of the way a good theory is supported by available evidence. At the time that Darwin’s Origin of the Species was published, so too was information about the fossil record that supported the idea of gradual evolution. This evidence, combined with Darwin’s research, led to other scientists looking into the phylogenies (evolutionary pathways) of species. It was seen that they conformed to Darwinian predictions and so lent support to the theory. In each case, Darwin’s evidence for evolution has been rigorously tested, and it stood up to this test. What is also extremely important is that Darwinian theory can be applied in countless situations – the tenrecs of Madagascar, the finches and turtles of the Galapagos, the rhea of the Magellan Straits and the list goes on. In each case, the unique characteristics of these organisms can be explained using Darwinian histories.

|

Questions at the time that were unanswered by the claims

of Darwinian theory have since been investigated and answers

found to be consistent with Darwin’s theory. For example,

until quite recently, the mechanisms of genetic inheritance

were not understood. Had they contradicted the Darwinian

model, it would have been necessary to modify the theory.

However, these mechanisms are now explained and fit the

model of Darwinian evolution, making sense of the spread

of advantageous variations, not only complementing but

also giving strength to the theory. This result exemplifies

what Kitcher refers to as the “predictive success” of

good science.

If we concede (as most scientists do) that there is only

a reasonable model for scientific method rather than a

clear demarcation, and that scientific theory is ‘good’

when it fits the mould of this model, we can see that

Darwin’s account of evolution, while ‘just a theory,’

can be counted as a good and believable one. While there

is debate among evolutionary biologists as to whether

Darwin’s gradualism is the best explanatory mechanism

for change, there has been no conclusive test (scientific

or otherwise) that discredits the claims of Darwinism.

We must hope that, in the spirit of science, when such

a test occurs, evidence will sustain Darwinian theory

or move us on to a new theory.

As it stands, Darwinism fits the mould of good – and

believable -- science. It consists of auxiliary hypothesis

that are testable. It makes claims that lead to further

research. It currently explains and fits available evidence.

As most scientists believe, a theory’s task is to help

solve both the empirical and conceptual problems that

scientists encounter. Presently, Darwinian theory does

just that. As far as claims of ‘scientificity’ go, evolutionary

theory today rests on a long record of successes. An argument

that will change the minds of those in the scientific

community has yet to be offered by those favouring Intelligent

Design or other anti-evolutionist perspectives.

Want to hear more about Evolution?

Click Here  (Courtesy of Wikipedia)

(Courtesy of Wikipedia)

Duration: 34mins 27sec (file size 5.91Mb and may be slow to download for dial-up users)

Ellie Pratt is a second year Science/Arts

student at the University of New South Wales. She is majoring

in History and Philosophy of Science as well as Microbiology

and Immunology, and she is interested in doing research

involving Antarctic ecosystems.

This article was originally written as

an essay for the School of History and Philosophy of Science

at the University of New South Wales.

Background Reading:

Ayer, A., J., Wittgenstein, Popper &

the Vienna Circle, Philosophy in the Twentieth Century,

London: Unwin, 1982, 108-141.

Bechtel, W., Post-Positivist Philosophy

of Science, in Philosophy of Science, Hillsdale: Lawrence

Erlbaum, 1988, 50-70.

Blackwell, R., Could There be Another

Galileo Case? in P. Machamer ed., The Cambridge Companion

to Galileo, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998,

348-366.

Gillies, D., Is Metaphysics Meaningless?

in Philosophy of Science in the Twentieth Century, Oxford:

Blackwell, 153-188.

Gish, D., T., Evolution: The Challenge

of the Fossil Record, San Diego: Creation-Life Publishers,

1985.

Gould, S., J., Evolution as Fact and Theory,

Discover, May 1981. Reprinted in A. Montague ed. Science

and Creationism, Oxford, 1984, 117-125.

Kelvin, Lord., Wave Theory of Light, Lecture

Delivered Before The Academy Of Music, Philadelphia, Under

The Auspices Of The Franklin Institute, 29 September,

1884, printed in the Journal of the Franklin Institute,

November 1884, 118: 321-341. Accessed online http://zapatopi.net/kelvin/papers/wave_theory_of_light.html on Friday, October 21, 2005.

Laudan, L., The Demise of the Demarcation

Problem, Physics, Philosophy and Psychoanalysis, ed. R.

S. Cohen and L. Laudan, Reidel: 1983, 111-27.

Morris, H., M., Scientific Creationism,

San Diego: Creation-Life Publishers, 1985.

Ruse, M., Can a Darwinian be a Christian?,

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Stockwell, J., Borel’s Law and the Origin

of Many Creationist Probability Assertions, in the Talk.

Origins Archive. Accessed online

http://talkorigins.org/faqs/abioprob/borelfaq.html on Friday, October 21, 2005.

OnSET is an initiative of the Science Communication Program

URL: http://www.onset.unsw.edu.au/ Enquiries: onset@unsw.edu.au

Authorised by: Will Rifkin, Science Communication

Site updated: 7 Febuary, 2006 © UNSW 2006 | Disclaimer

OnSET is an online science magazine, written and produced by students.

![]()

OnSET Issue 6 launches for O-Week 2006!

![]()

Worldwide

Day in Science

University

students from around the world are taking a snapshot

of scientific endeavour.

Sunswift

III

The UNSW Solar Racing Team is embarking

on an exciting new project, to design and build the

most advanced solar car ever built in Australia.

![]()

Outreach

Centre for Sciences

UNSW Science students can visit your school

to present an exciting Science Show or planetarium

session.

![]()

South

Pole Diaries

Follow the daily adventures of UNSW astronomers

at the South Pole and Dome C through these diaries.

News in Science

UNSW is not responsible for the content of

these external sites