Face

Transplants: The

Cutting Edge of Ethics

Adrian Pokorny

While the idea of a face transplant

may sound ludicrous, it is the next step in the evolution of transplantation,

helping those with severe facial injuries. While light hearted in tone,

the article examines some pertinent issues in medical science today.

There has been a lot of talk recently about face transplant operations.

The topic is being discussed in detail throughout the scientific and wider

community as everybody continues to reflect on the first face transplant,

recently performed in France. It is now obvious that while the technical

science behind a successful transplant is possible, not everyone inside

and out of the scientific community support the procedure. Why you may

ask? What is the dilemma in allowing an injured person to regain a sense

of normality? The answer lies in ethics.

The theoretical ethics of most organ transplants were dealt with decades ago, with the general consensus being that the benefits of prolonged life (or, indeed, quality of life) outweigh the moral issues associated with removing organs from the recently deceased.

This result may be understandable, as to live with someone else’s liver or kidney takes very little adjustment at all. Generally, people are not aware of their viscera and, when they are, it is more than likely that their perception has been influenced by, shall we say, chemicals of the psychotropic variety. For most transplants, the new organs themselves are never thought of, with only the associated benefits able to be noticed. Basically, “out of sight out of mind” holds true, and the ethics slide right by. More recently, other parts of the human anatomy have been swapped between bodies for which this situation is not the case. The most famous examples are the transplantation of the voice-box and, of course, the forearm.

In a visual sense, the forearm transplant, first performed less than a decade ago, is by far the oddest looking despite the sophistication of modern science. When screening for a transplant, genes are matched on the basis of rejection. That is, a patient is matched with a donor organ that he or she has the least chance of rejecting immunologically. They are not matched on the basis of skin colour, body fat content, hairiness, etc. Therefore, the physical contrast in such patients is immediately apparent, most obviously to the patients themselves.

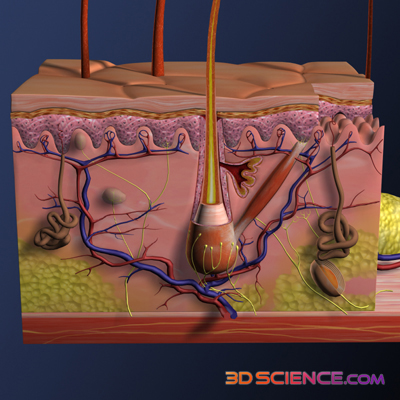

|

Cross section of skin. |

While skin colour may vary slightly with time, and the science of hair removal is now more advanced than the space program, the visual differences will remain leaving the patient to contemplate living with what, essentially, is the arm of a dead man. In addition, the transplanted arm will never be of the same functional quality as the original arm, which puts into question the practical value of these early operations. When all these factors are combined, the situation may be confronting to say the least, leaving some arm-transplant patients to cease immunosuppressant medication in order to induce the need for amputation. If such intense personal discomfort is possible with a new arm, all external transplants must be scrutinised to as great an extent as is possible.

But not all the transplants in this category turn out poorly. The aforementioned voice-box transplant, though rare, has shown immense potential and benefit to recipients. Like many of the face transplant questions, the main ethical dilemmas of voice-box transplants revolve around just how much of the new voice belongs to the donor and how much to the recipient. Unfortunately, for all those out there who were hoping to sound like Frank Sinatra the easy way (or the hard way depending on your interpretation of major surgery), it appears that -- over time -- the voice of the patient post-transplant becomes almost exactly like his or her original voice.

Macabre cosmetic surgery dreams aside, such outcomes are actually very good news as they overcome a major ethical hurdle. If the new voice-box sounds just like the old voice-box, it becomes, in a way, just like any other transplant of an internal organ. That is to say, the new organ can be ignored most of the time and only really thought about when discussing the struggle of it all on Oprah or, much more possibly, Australian Story. While the concept of taking someone else’s voice-box is still a bit much for some to sweep aside simply, transplants to which a patient can generally pay no attention are definitely the winners of the Ethics Awards, at least from the point of view of a recipient patient.

If only such acceptability were as viable for face transplants. Both the voice and the face are inherent aspects of character, which explains why their ethical issues are almost identical. To much disappointment, but not a great deal of surprise, our whole body is not quite as good at influencing our facial structure as it can influence the sound of our voice. Because of this deficiency, an immediate question surrounding the transplants is just how much the recipient will resemble the donor.

After practising numerous face transplants on cadavers, a team of doctors came to the conclusion that the new face would appear to be about 60% that of the recipient and 40% that of the donor. It is anyone’s guess just how they came up with a system that could measure facial similarities in percentages. However, the point is that the new face does not resemble either party completely. Instead being a mixture of the two, it leans quite clearly on the side of the recipient. Hence, John Travolta and Nicolas Cage exchanging faces completely in the movie Face Off would be impossible, in reality a mixed Nicholas Cage/John Travolta face would form – how bizarre!

It is interesting to note how the face, while by all definitions an external transplant, does not create the intense contrast of skin colour or type that was so apparent in the forearm transplant. Presumably this is because the face is a singular entity, existing almost removed from most other skin areas. It does not look particularly strange for a face to be different to the rest of the body as there is nothing with which to really compare it. Many a person has come back from the beach, their face a few shades darker than the rest of their body. This is an advantage as it means the new face would not seem odd to any stranger viewing it, aiding in the assimilation of the recipient patient.

In any case, the 60/40 phenomenon leads to an ethical grey-area. The idea of a mixture face is either better or worse than either option, but there is quite a bit of disagreement as to which side it actually falls on. Probably the best way think about this issue is in terms of the way the appearance of the new face would be perceived by a patient, the rule of thumb for many transplant questions. The appearance of the new face will not be the same as their original face; this much is clear. It will also not be so different that they will not recognise any aspect of their features; this is also acknowledged. How any individual will perceive the differences or similarities is the big problem and psychologically the most difficult issue to analyse pre-operatively.

There is another option. That is to leave the patient without a face or, more accurately, with a facial area covered in scar tissue. This is the only real alternative for the candidate patient. It is important to remember this option as it is without a doubt a more distressing position for most patients than to have to deal with the differences that may be present in a donor face.

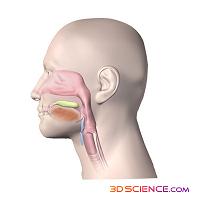

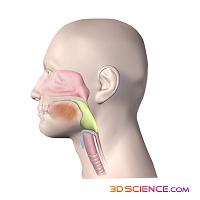

Apart from the physical issues associated with having no face, such as the inability to eat properly, cry and feel sensation to any great extent, the psychological issues are enormous.

|

| The Three Stages of Swallowing Courtesy of 3D Science |

An individual’s face is central to their sense of identity. This is different, though not totally removed, from whether or not they find themselves attractive. One’s physical sense of self is taken for granted in most people, but its removal may have devastating consequences for their well being. Lack of a face also has been shown to drastically slow the entire recovery process, a fact of great relevance to those involved in accidents that remove the face. It is more often the case that the patient is involved in a whole body incident, such as a car crash or fire, which causes systemic injury. Recovery in such occurrences requires absolute mental commitment or involvement, something that may be jeopardised in patients troubled by loss of a key external aspect of their sense of identity, their face.

It is because of such issues of identify that the concept of face transplants is receiving much attention from the medical and scientific community. If the benefits could be realised, the quality of life for thousands of people could be unimaginably improved, which really is the goal of medicine. The ethical questions are many and should not be ignored, but as time goes on, improvements in method or visualised results may make a lot of the questions easier to answer. There may very well be a time when this procedure becomes standard practice as a solution for those devastated by a loss of their face.

Adrian Pokorny studied for a Bachelor of Science at the University of New South Wales and is currently pursuing Medicine at the University of Newcastle, Australia. Interested in all of the weird and wonderful aspects of science, Adrian is unsure in which area he should specialise.

OnSET is an initiative of the Science Communication Program

URL: http://www.onset.unsw.edu.au/ Enquiries: onset@unsw.edu.au

Authorised by: Will Rifkin, Science Communication

Site updated: 7 Febuary, 2006 © UNSW 2006 | Disclaimer

OnSET is an online science magazine, written and produced by students.

![]()

OnSET Issue 6 launches for O-Week 2006!

![]()

Worldwide

Day in Science

University

students from around the world are taking a snapshot

of scientific endeavour.

Sunswift

III

The UNSW Solar Racing Team is embarking

on an exciting new project, to design and build the

most advanced solar car ever built in Australia.

![]()

Outreach

Centre for Sciences

UNSW Science students can visit your school

to present an exciting Science Show or planetarium

session.

![]()

South

Pole Diaries

Follow the daily adventures of UNSW astronomers

at the South Pole and Dome C through these diaries.

News in Science

UNSW is not responsible for the content of

these external sites