Why Brewing A Bathtub Full of Wine and Then Drinking All Of It Can Be Bad

Lindsey Wu

QUEEN ELIZABETH HOSPITAL, ADELAIDE: A man was admitted into hospital showing signs of severe lead poisoning. The concentration of lead in his blood was found to be 980μg per litre, several times the maximum concentration considered to be dangerous. The source of the lead poisoning? No, it wasn’t the leaded petrol he put in his car, he hadn’t been sucking on lead sinkers, and he hadn’t ever worked in a lead mine. He’d been home-brewing, using his old lead-lined bathtub at home as a primary fermentation vessel. For those not in the know when it comes to home brewing, in the primary stage of fermentation, fruit, sugar, water and yeast are mixed together, usually in some kind of an appropriate container, like a food grade bucket, and allowed to ferment for around a week, before the wine is moved to secondary fermentation to remove sediment, and then bottled. Throughout the process, one has to be careful to ensure all containers are sterile.

Rather than do this, the 66-year old home brewer added crushed grapes, sugar, water and yeast directly into his bathtub, and allowed it to ferment, before siphoning the concoction directly into bottles. Whilst the wine was fermenting in the bathtub, the pH decreased to around 3.8, not unusual, as the pH of wine varies between 3.5 and 4. This low pH, however, dissolved the enamel of the bathtub, exposing the lead surface, which had been heavily corroded. Testing of the wine showed that the lead concentration was around 14mg per litre. The legal limit for lead in red wine is 0.2mg per litre.

History of Lead Poisoning

Although this man had a bit of bad luck with his home brew it seems that getting lead poisoning from wine wouldn’t have been so strange back in roman times. Lead toxicity was first recognized as early as 2000 BC. The occurrence of Gout a type of arthritis among the affluent in Rome was thought to be the result of lead, or leaded, eating and drinking vessels. Lead was also used in makeup and to sweeten wine. In 17th-century Germany, a physician noticed that monks who did not drink wine were healthy, while wine drinkers developed colic. The culprit was a white oxide of lead, litharge, added to sweeten the wine.

Today, most exposure in developed countries is the result of occupational hazards, leaded paint, and leaded petrol (which continues to be phased out in most countries).

Symptoms and effects

The symptoms of lead poisoning include neurological problems, such as reduced IQ, nausea, abdominal pain, irritability, insomnia, excess lethargy or hyperactivity, headache and, in extreme cases, seizure and coma. There are also associated gastrointestinal problems, such as constipation, diarrhea, abdominal pain, vomiting, poor appetite, weight loss. Other associated affects are anemia, kidney problems, and reproductive problems. In humans, lead toxicity often causes the formation of a bluish line along the gums, which is known as the "Burtons's line".

Biological Role

Lead has no known biological role in the body. The toxicity comes from its ability to mimic other biologically important metals, the most notable of which are calcium, iron and zinc. Lead is able to bind to and interact with the same proteins and molecules as these metals, but after displacement, those molecules function differently and fail to carry out the same reactions, such as in producing enzymes necessary for certain biological processes. Most lead poisoning symptoms are thought to occur by interfering with an essential enzyme Delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase, or ALAD. ALAD is a zinc-binding protein which is important in the biosynthesis of heme, the cofactor found in hemoglobin. Genetic mutations of ALAD cause the disease porphyria, a disease which was highlighted in the movie The Madness of King George.

|

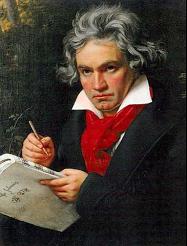

| Scientists confirmed in 2005 that Ludwig von Beethoven died of lead poisoning by x-ray analysis of fragments of his skull and hair. This portrait of Beethoven was painted by Karl Stieler in the 1820s. |

Famous Cases of Lead Poisoning Many historians have believed that Ludwig van Beethoven suffered from lead poisoning. This belief has been confirmed in 2005 by tests done at Argonne National Laboratory in the US on skull bone fragments, confirming earlier tests on hair samples. “There are many possibilities," says Bill Walsh, who headed a team that studied Beethoven's hair samples and fragments from his skull at the Department of Energy laboratory in Argonne, USA. The composer was a wine lover, and wine at the time was known to contain high lead levels. He also drank out of a goblet made partially of lead and stayed at a spa where he drank mineral water, Walsh says. (http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5041495)

For more information see:

http://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/docs/2001/109p433-435mangas/abstract.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lead_poisoning http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/12/05/AR2005120501937.html

OnSET is an initiative of the Science Communication Program

URL: http://www.onset.unsw.edu.au/ Enquiries: onset@unsw.edu.au

Authorised by: Will Rifkin, Science Communication

Site updated: 7 Febuary, 2006 © UNSW 2006 | Disclaimer

OnSET is an online science magazine, written and produced by students.

![]()

OnSET Issue 6 launches for O-Week 2006!

![]()

Worldwide

Day in Science

University

students from around the world are taking a snapshot

of scientific endeavour.

Sunswift

III

The UNSW Solar Racing Team is embarking

on an exciting new project, to design and build the

most advanced solar car ever built in Australia.

![]()

Outreach

Centre for Sciences

UNSW Science students can visit your school

to present an exciting Science Show or planetarium

session.

![]()

South

Pole Diaries

Follow the daily adventures of UNSW astronomers

at the South Pole and Dome C through these diaries.

News in Science

UNSW is not responsible for the content of

these external sites