| ONSET |

| Transplants: The Cutting Edge of Ethics | ||

| Many of us would accept someone else's liver or kidney if we needed it. but what about their voicebox, arms or face? | ||

|

|

||

|

||

|

In recent years there has been a lot of talk about the success of the world's first face transplants. While scientific techniques make these transplants possible, not everyone in and out of the scientific community supports the procedure. "But why?" you might ask. What is the dilemma in allowing an injured person to regain a sense of normality? The ethical issues surrounding organ transplantation have been debated for decades, with the general consensus being that the benefits of prolonged life (or, indeed, quality of life) outweigh the moral issues associated with removing organs from the recently deceased. When you are living with someone else's liver or kidney, you will notice the improvements that your new organs bring to your health. But the organs themselves are hidden from sight. Basically, “out of sight out of mind” holds true, and the ethics slide right by. But recently, more percievable parts of the human anatomy have been swapped between bodies. One example is the transplantation of the forearm. When screening for a transplant, genes are matched on the basis of rejection. That is, a patient is matched with a donor organ that he or she has the least chance of rejecting immunologically. They are not matched on the basis of skin colour, body fat content, hairiness, etc. So the physical contrast in such patients is immediately apparent, especially to the patients themselves.

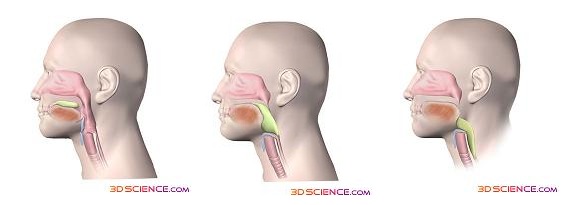

Despite advances in cosmetic surgery, these physical contrasts can be a continual reminder to the patient that they are living with what is essentially the arm of a dead person. In addition, the transplanted arm will never be of the same functional quality as the original arm, which calls into question the practical value of these early operations. When all these factors are combined, the situation may be confronting. Some arm-transplant patients have been known to cease taking immunosuppressant medication in order to induce the need for amputation. If such intense personal discomfort is possible with a new arm, external transplants must be scrutinised heavily. This is not to say that all external transplants are quite so intrusive. The voice-box transplant, though rare, has shown immense potential and benefit to recipients. As with face transplants, there is a concern of how much of the new voice belongs to the donor and how much to the recipient. Unfortunately, for all those out there who were hoping to sound like Frank Sinatra the easy way (or the hard way, depending on your interpretation of major surgery), it appears that -- over time -- the voice of the patient post-transplant becomes almost exactly like his or her original voice. What about face transplants? Disappointingly, our whole body cannot influence our facial structure as much as it can influence the sound of our voice. This leads to a question; to what extent will the recipient resemble the donor? After practising numerous face transplants on cadavers, a team of doctors came to the conclusion that the new face would appear to be partly that of the recipient and partly that of the donor. So the new face does not resemble either party completely. Hence, John Travolta and Nicolas Cage exchanging faces completely in the movie Face Off would be impossible - in reality a mixed Nicholas Cage/John Travolta face would form! Often, the only real alternative to this option is to leave the patient with a facial area covered in scar tissue. This is understandably a much more distressing position for most patients. Apart from the physical issues associated with having no face, such as the inability to eat properly, cry and feel sensation to any great extent, the psychological issues are enormous.

An individual’s face is central to their sense of identity. While many of us take our physical sense of self for granted, its removal can have devastating consequences for our well being. Lack of a face also has been shown to drastically slow the entire recovery process. This is especially important because most accidents that remove the face tend to be whole body incidents that cause systemic injuries to other parts of the body, such as car crashes and fires. Recovery requires a resolute mental commitment from the patient, something that may be jeopardised when they are troubled by the loss of a key aspect of their sense of identity, such as their face. These issues are giving transplants a lot of attention from the medical and scientific community. But as time goes on, improvements in method may make a lot of the ethical questions easier to answer. If the benefits could be fully realised, quality of life for thousands of people could be drastically improved, which is the goal of medicine. There may very well be a time when these procedures become a standard solution for those who suffer from devastating personal injuries. Adrian Pokorny studied for a Bachelor of Science at the University of New South Wales and is currently pursuing Medicine at the University of Newcastle, Australia. Interested in all of the weird and wonderful aspects of science, Adrian is unsure in which area he should specialise. |

||